A Call For Climate Justice

“Climate Justice,” in Systemic Crises of Global Climate Change: Intersections of Race Class, and Gender, Phoebe C. Godfrey & Denise Torres, eds. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Social justice activists are the hope of the environmental movement because the climate crisis will not be averted without a major re-structure of our economic, social and political systems.

Remember how citizens of the United States became discarded refugees in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina?[i] African Americans were rounded up and tightly packed into the Superdome, as in some monster slave ship of the infamous Middle Passage on the ocean of flood waters. They were held like captives in slave-pens, without food and water for days, awaiting the slow-to-arrive school buses that would disperse them throughout a land far away from their homes. Some tried to walk out of the flood- ravaged city, rather than wait to drown or die of thirst as our government did nothing. Crossing the Crescent City Connection, the bridge that links the city of New Orleans with the west bank of the Mississippi and the predominantly white town of Gretna, they were met with shotgun fire from White Gretna city police. The group of hundreds of predominantly Black citizens stopped at the fire of warning shots. They were instructed that they could not cross. Not knowing where to turn, they began to set up camp on the middle of the bridge. A Gretna police officer yelled at them through a bull horn “Get the f*** off the bridge.” Someone asked why they couldn’t pass on to safety. They were told that “there will be no Superdome here.”[ii]

Citizens, who by definition have the constitutional right to travel, who reasonably rely on their own government to help them in a crisis, lost their citizenship rights that night. From the perspective of civil rights and social justice, the entire Hurricane Katrina fiasco was one enormous abrogation of citizenship resulting in death and displacement. A complete betrayal. I remember the shock I felt when I heard news reporters actually refer to the residents of New Orleans as “refugees.”

As an African American woman and direct descendant of slaves, I am constantly attuned to the fact that people are used and discarded. I was born into a family of activists, and taught that the only way to survive is to fight back. My father was the child of slaves—both his parents were born in 1860, my grandmother Harriet Thorpe was born the property of Squire Sweeney in Howard County, Missouri and my grandfather Haywood Hall was born the property of Colonel Haywood Hall on his plantation in Tennessee. I never met either of them—they died long before I was born in 1963. My dad was the youngest of the Hall family’s children, born in 1898. He never finished eighth grade and worked odd jobs, from shining shoes to waiting tables. Unable to tolerate or comply with racism, he worked outside the system. He was labor organizer, a communist and a self-taught worker-intellectual, publishing two books and numerous articles during his life. In 1956 my parents were forced to travel to three different states before they could find a judge to marry them—my mom a second generation White New Orleanian Jew of Russian and German descent, my dad African American and 33 years her senior. My mom had begun her work as an anti-racist activist when she was a teenager in the 1940s and never looked back. She was a teacher and later a professor of history and has written 3 books on the history of slavery. My parents were black-listed during the McCarthy era and forced to flee the country, which is how I ended up being born in Mexico City and having dual citizenship.

It was Hurricane Katrina that woke me up to the climate crisis, and when I think about it, I immediately think of all the disposable people—the half the planet who are already barely surviving. What will happen when the levees break again?

Pacific Island nations face the destruction and inundation of their lands caused by rising sea levels. There are over 7 million Pacific Islanders who live in 22 nations. The Prime Minister of Tuvalu explains that his nation was being destroyed by climate change, which represents an unprecedented threat to Tuvalu’s “fundamental rights to nationality and statehood, as constituted under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other national conventions.”[ii] After a long fight against slavery and imperialism, after finally gaining their sovereignty in 1978, the First World’s consumption of fossil fuels will take their country away again.[iii] It is enough to make a grown woman cry.

In 2007 a record was set: human-caused global warming caused the melting of 42% of the Arctic ice cap. That record was broken in 2012, and scientists predict that the Artic will be ice-free in 20 years.[iv] Storms are getting fiercer. Hurricane Sandy appeared soon after that record was broken. Sea levels are rising. I grew up in New York City, and watching the videos of water pouring into the subways and Path train terrified me. My mom, who grew up in New Orleans and live in New York for many years, called me crying and said both of her home places were being destroyed.

95% of the world’s glaciers are in retreat.[v] And the snow pack is melting in places where people depend on its water for agriculture and drinking water.[vi] And already Pacific Islanders are preparing to relocate, to leave their countries underwater and be cast on the mercy of other nations. Who will take them in? Friends of the Earth International and the Australian Refugee Council are urging Australia to step up, to include the category of “climate refugee” into their asylum program.[vii] The current categories used world-wide, written in the wake of World War II were designed to protect those who are in fear of persecution by their government because of their race, religion or nationality. There is no system in place to handle those forced to leave their nations because of climate change. My fear is that they will continue to be treated as so-called “economic refugees,” people by definition who won’t be helped. We in the Global North have no responsibility for people who are in trouble because their economic systems failed them, right? Some scientists estimate that all of the world’s mountain snowpack will be gone by 2030. What happens to the billions of people who need that water to drink and grow food with? What will happen when 7 million Pacific Islanders, along with the millions of citizens of the low lying river deltas throughout the world, lose their citizenship along with their nationhood? Will we watch the flags of country after country lowered in front of the United Nations? What will these people be when they are stateless? What will the first world do with all of these stateless people of color from other lands? The U.S. government would not help its own citizens in New Orleans, never mind racialized others who aren’t even from here. In 2005 we saw how, within days, African Americans in New Orleans lost their citizenship, as if some Frankenstein-like Chief justice Taney rose from the dead declaring a new Dred Scott decision.

In 2012 the Northeast was hit by the monster Hurricane Sandy, and we saw there that even in the richest part of the world, government and humanitarian response systems were overwhelmed, and it mattered what neighborhood you lived in, and what your race or class was. What happens when we have super storms every year? It will be a world-wide Dred Scott, as the first world proclaims that the people of the global South have no rights “which the white man is bound to respect.”[viii]

What can we do? It is not too late to preserve a livable future for humans on this planet, but our window of opportunity is closing. NASA’s top climatologist, James Hansen, explains that if we stop the use of coal within the next two decades, phase out the use of conventional petroleum and ban the use of high-carbon fuels like shale and tar sands, we have a chance to bring greenhouse gasses back down to safe levels.[ix] We may not be able to reverse the extensive damage already done, but we can prevent it from getting any worse.

How do we do it? We need more environmentalists to reframe this whole issue of climate crisis as one of social, economic and racial justice—no small task, but some groups on the more radical end of the environmentalist movement are trying. Here I am calling on all of us at the other end of this intersection, the social and economic justice activists. Over the past three decades the central concept of intersectionality—the ways in which race, class and gender are mutually constituted and can only be dismantled together—have worked its way into the theory and practice of economic and social justice. Now we need to understand that the climate crisis is the most urgent and deadly issue facing women, poor people and communities of color today. We must understand that “the environment” is not something “out there” that we can think about after we deal with poverty, racism, institutionalized male dominance and heterosexism. The environment is where we live and breathe, it is literally the ground on which we stand and fight. We need a climate justice movement, which understands and addresses this intersection.

This movement for climate justice is not merely additive. We don’t just join the environmental movement, We redefine it and restructure it. In fact, social justice activists are the hope of the environmental movement because the climate crisis will not be averted without a major re-structure of our economic, social and political systems. If the standard of success is preserving the earth, the environmental movement and environmentalism has been a failure.[x] It has been trapped in a world of policy strategies while the democratic system needed to actualize these approaches has collapsed under the weight of corporate capitalism. It has gone along with the prime directive of unbridled growth and all of its sick sequelae that are fundamentally at odds with living on a planet with limits. A climate justice movement will instead demand advancing democracy as well as the health and welfare of the people within systems that will sustain the people and the planet. Environmentalism has tried change within a system that is designed to “externalize” the real costs of business as usual—whether that is the burden of subsidizing workers who are paid poverty wages without benefits, or the destruction of local and global ecosystems by international corporations that go wherever they want, leave behind whatever disasters they make, while creating corporate refugees—people who are being destroyed by this economy. And unlike corporations, they’re not allowed to cross borders.

When we demand that our leaders bring carbon emissions back to safe levels, we are requiring them to put the interests of people before the richest corporations in the world. It will require a drastic restructuring of our economy, and provide an opportunity to recreate it in a more just and equitable way. We have moved past environmentalism. The call now is for climate justice, and we all must become climate justice activists.

Rebecca Hall, J.D.; PhD

Rebecca is an attorney, scholar and life-long activist. She has been arrested eight times in the anti-nuclear movement, the anti-Apartied movement, the anti-war movement, and once by accident when the police arrested the legal observers before they arrested the protesters. She got her law degree from U.C. Berkeley and worked for many years in housing rights. She went back to school for a PhD in history in order to better understand the intersections of race and gender and to teach, but has had no success in breaking into the elite club of tenure track professors. Rebecca has published on African American women’s freedom movements, from slave revolts to Reconstruction, and has been an organizer and trainer with Peaceful Uprising since 2009.

[i] For more discussion of this, see my essay “Hurricane Katrina: The New Dred Scott, “in Hurricane Katrina: Response and Responsibilities, John Brown Childs, ed. New Pacific Press, January, 2005.

[ii] Apisai Ielemia, “A Threat to Our Human Rights: Tuvalu’s Perspective on Climate Change,” June 2007 (http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1309/is_2_44/ai_n27399052/pring?tag=artBody;col1) For up to date information on Tuvalu and it’s people’s forced relocation to New Zealand, see http://www.tuvaluislands.com/warming.htm

[iii] According to the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) the Pacific Island nations contribute 0.06 percent to global greenhouse gas emissions but are three times more vulnerable to climate change than countries of the global North. http://www.solomontimes.com/news.aspx?nwID=3371

[iv] The Guardian http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2012/sep/14/arctic-sea-ice-smallest-extent

[v] James Balog, Extreme Ice Now. (Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2009), p.38

[vi] http://www.highroadforhumanrights.org/documents/speeches/071308climatechangeashumanrightsissue1.pdf, p8.

vii (http://www.foei.org/en/get-involved/take-action/archived-cyberactions/climate-refugees)

[viii] Scott v. Sanford, 60 U.S. 393 (1857)

[ix] http://solveclimate.com/blog/20090710/g8-failure-reflects-congress-failure-write-effective-climate-policy

[x] . ( Many environmental “insiders” and strategists agree with this assessment. See generally James Gustave Speth, The Bridge at the Edge of the World: Capitalism, the Environment and crossing from Crisis to Sustainability. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2008.)

Abolish Fossil Fuels!

We need to learn from social movement history to understand that attaining climate justice requires a radical paradigm shift. The Big Green strategy of working within the regulatory system has failed miserably on multiple levels. The fossil fuel industry runs the world government and the world economy and is rapidly destroying our planet. Climate justice activists need strategies that are commensurate with the depth and severity of the problem. We need a multinational direct action campaign to abolish fossil fuels.

How do Activists use Social Movement History?

What lessons can be learned from past movements for social change in our fight to stop climate change? We often rely on lessons and tactics from the U.S. Civil Rights movement. We think this might be the best source for our lessons from the past.

Think again.

How about the Abolition of the Slave Trade? As an activist, I fight for climate justice. As an historian and a scholar of law and history, I study slavery and the slave trade.

The movement for civil rights—certainly the mainstream movement—was based on the perceived need to have equal rights in an existing system. The right to vote, the right to fair housing. An end to segregation. Integration into the existing status quo at every level. And none of these things are bad things. Having equal rights is better than not having equal rights. But even the more radical wing of the civil rights movement questioned these goals. SNCC members famously asked, “Do we really want to die for the right to vote?”

The movement for climate justice is different. We are demanding “system change, not climate change.” We are not fighting for access to an existing status quo. We are demanding a fundamental restructuring of society in order to have the possibility of a livable future. So let’s look at social movement history that might be more analogous.

The Atlantic Slave Trade—A World Economic Order

The movement to abolish the Atlantic Slave Trade was a movement to end an entire economic system. The Atlantic Slave Trade, the largest forced migration of people in human history, occurred between the mid-fourteen hundreds to the mid-eighteen hundreds. It is estimated that between 30 and 60 million Africans were trafficked, and it was a deadly enterprise. African captives died on forced marches to the coast, in slave pens on the African littoral, on ships during the “middle passage,” and during their first year of “seasoning” in the Americas. At least 40% of the Africans caught up in the trade were killed by it. This trade had a profound demographic impact on both Africa and the Americas. By the end of the Trade, West and West Central Africa were close to the brink of demographic exhaustion, which left it unable to resist the colonial exploitation and resource extraction that began in the mid-nineteenth century.

The Atlantic slave trade was carried out by shifting European naval powers, each of whom overlapped, but gained ascendancy in different time periods. The Portuguese were first, then the Dutch. The Spanish and the French became involved, and the English began trading in large numbers during the late 17th and early 18th centuries. England was by far the largest trader in terms of sheer numbers.

Abolition

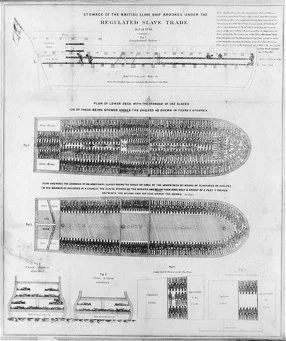

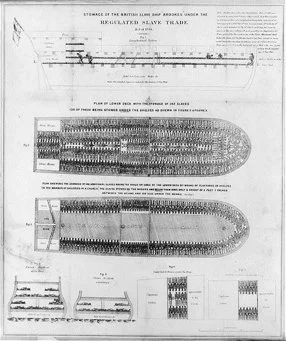

The Atlantic Slave Trade grew exponentially between the last decades of the 1600s and the first years of the 19th century, and the movement for the abolition of slavery and the slave trade grew along with it. If we are taught the history of Abolition at all, we are taught about British elite actors, men who were opposed to slavery and the slave trade on religious and moral grounds, and fought within the system for legal approaches to end the slave trade. Some fought for abolition, some for mere amelioration, regulating how many people can be packed into slave ships, and so on. This famous diagram is from a law passed to make the slave trade more humane, and illustrated the maximum number of slaves allowed on a ship.

Brookes Diagram

Yes this shows what was legal. Evil can be regulated, if that is where you want to put your energy. Slave Ship Revolts: Abolition from the Bottom Up.

But other actors were just as crucial: Wide-spread direct action campaigns, organizing boycotts of sugar and cotton and other slave produced goods. Free people of African descent who fought slavery and the slave trade by any means necessary. African captives on who led revolts on slave ships—men and women who refused to be cargo. Recent studies show slave revolts on one in ten voyages, and this caused a sharp increase in the carrying costs of the trade, helping to undermine its economic viability. And Africans on the coast that attacked slave ships before they sailed, cutting them off and freeing captives.

Economic Conflict and Economic Change

There were other forces that brought about abolition as well—more cynical forces. At the U.S. constitutional convention, colonies in the upper south, especially Virginia, wanted the Atlantic slave trade to end, because Virginia made its money in the domestic trade, breeding slaves and selling them “down the river” (yes, that is where that expression comes from). The result was the slave trade clause of the U.S. Constitution, Article I section 9, which made it that the trade could not be abolished until 1808. (Look it up, it is still there). And there were the big picture changes in the world economy. Four hundred years of slavery and the slave trade allowed for the capital accumulation needed to spark and fund industrialization, and capitalism needed something else. It would not grow by sticking to a proto-industrial agrarian plantation economy. The next stage needed factory workers, “free labor,” and the colonization of Africa and Asia in order to extract the resources needed to industrialize. And let us not forget that England got to position itself as the naval police force of the Atlantic in its effort to suppress the trade. England did in fact “rule the waves.” All of this brought an end to the Atlantic Slave Trade, abolished in 1807 in England, 1808 in the U.S., and world wide by 1830.

Abolish the Fossil Fuel Economy

What can we learn from this social movement history? It never works to take the past and graft it on to the present, but past can be prologue. What can we learn by shifting from a Civil Rights paradigm of social change, to an abolitionist one? Doing this shift will help us critically engage with the strategies of the climate justice movement. Bill McKibben’s groundbreaking article “Global Warmings’s Terrifying New Math,” http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/global-warmings-terrifying-new-math-20120719 helped launch a nationwide university divestment campaign, drawing on the successful strategy of the anti-Apartheid movement. Climate justice activists need more strategies that are commensurate with the depth and severity of the problem. We need a multinational direct action campaign to abolish fossil fuels.

(I first presented the “Abolition of fossil fuels” paradigm as in Peaceful Uprising’s first Climate Justice Bold School training in October of 2012 on social movement history.)

Self-Defense, Non-Violence and the Diversity of Tactics

(This essay was written in 2017) There is a lot of discussion about non-violence as a moral belief, as a strategy, and as a tactic. I often see the following claim: “Non-violence is the only valid approach. Anything else must be disavowed as destructive to the resistance. Why, look how successful Martin Luther King was, and how seeing all those Black children brutalized on TV is what finally made Civil Rights happen.”

That is downright inaccurate historically. A lot of factors came together in the 1950s and 1960s that moved Civil Rights forward, and the tepidly moral outrage of Northern whites was a part, but only a part.

There were the decades of struggle of the African American people pushing towards the Civil Rights “era,” and that resistance took many forms.

There was the crucial fact that the United States was fighting the Cold War and trying to be the world’s face of Democracy for all of the decolonizing Third World, and seeing African Americans brutalized didn’t help their propaganda campaign. How many more countries in Latin America, Africa and Asia would they lose to the Soviet Union?

There was the other wing of the struggle for African American lives: The armed self-defense movement. Without it, the non-violent wing of the struggle would have not survived to fight back. This movement also continued to mobilize the parts of the African American community that practiced and believed in armed self-defense.

Understanding what is “violent” and what is “non-violent” is complex, and takes some sustained analysis. We live in a constant sea of violence.

Those communities not under attack have no right to argue that defending ourselves is immoral or non-strategic. Relying on moral suasion in a world that sees you as sub-human is a precarious proposition at best.

Suggested Readings

Civil Rights History 101: start here for basic historical literacy

I’ve Got The Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle, by Charles Payne

The best history I’ve read so far that explains the grass-roots nature of the Civil Rights Movement, and how it is grounded in decades of resistance. Be sure to read the historiographical essay at the end, “The Social Construction of History.”

The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women who Started It, by Jo Anne Gibson Robinson

Crucial book on how the Montgomery Bus Boycott was actually organized and sustained, it explains how Martin Luther King was brought in by the organizers to be the face of a movement he is now credited with creating.

Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement, by Barbara Ransby

“In this deeply researched biography, Barbara Ransby chronicles Baker’s long and rich political career as an organizer, an intellectual, and a teacher, from her early experiences in depression-era Harlem to the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Ransby shows Baker to be a complex figure whose radical, democratic worldview, commitment to empowering the black poor, and emphasis on group-centered, grassroots leadership set her apart from most of her political contemporaries. Beyond documenting an extraordinary life, the book paints a vivid picture of the African American fight for justice and its intersections with other progressive struggles worldwide across the twentieth century.”

Cold War and Civil Rights: Read these to understand this crucial issue.

Race Against Empire, by Penny Von Eschen

Race against Empire tells the poignant story of a popular movement and its precipitate decline with the onset of the Cold War. Von Eschen documents the efforts of African-American political leaders, intellectuals, and journalists who forcefully promoted anti-colonial politics and critiqued U.S. foreign policy. The eclipse of anti-colonial politics―which Von Eschen traces through African-American responses to the early Cold War, U.S. government prosecution of black American anti-colonial activists, and State Department initiatives in Africa―marked a change in the very meaning of race and racism in America from historical and international issues to psychological and domestic ones. She concludes that the collision of anti-colonialism with Cold War liberalism illuminates conflicts central to the reshaping of America; the definition of political, economic, and civil rights; and the question of who, in America and across the globe, is to have access to these rights.

Exploring the relationship between anti-colonial politics, early civil rights activism, and nascent superpower rivalries, Race against Empire offers a fresh perspective both on the emergence of the United States as the dominant global power and on the profound implications of that development for American society.

Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy, by Mary Dudziak

In what may be the best analysis of how international relations affected any domestic issue, Mary Dudziak interprets postwar civil rights as a Cold War feature. She argues that the Cold War helped facilitate key social reforms, including desegregation. Civil rights activists gained tremendous advantage as the government sought to polish its international image. But improving the nation’s reputation did not always require real change. This focus on image rather than substance–combined with constraints on McCarthy-era political activism and the triumph of law-and-order rhetoric–limited the nature and extent of progress.

Black Power and Armed Self Defense:

More is coming out every year on this topic. Get started on this repressed history.

Negroes with Guns: Robert F. Williams

The classic manifesto for armed self defense, written in 1962. Robert and Mabel Williams were dear family friends. An important read. Also, don’t miss his story told in an interview with his wife, Mabel, Robert F. Williams: Self-Defense, Self-Respect, & Self-Determination, as told by Mabel Williams

Radio Free Dixie: Robert F. Williams

The Deacons for Defense: Armed Resistance and the Civil Rights Movement, by Lance Hill

Annoyingly masculinist, but important nonetheless. More work needs to be done recovering women in the armed self-defense movement. Be sure to read the short conclusion, “The myth of non-violence.”

These are slightly later on the time line, but crucial:

Assata: An Autobiography, by Assata Shakur

“On May 2, 1973, Black Panther Assata Shakur (aka JoAnne Chesimard) lay in a hospital, close to death, handcuffed to her bed, while local, state, and federal police attempted to question her about the shootout on the New Jersey Turnpike that had claimed the life of a white state trooper. Long a target of J. Edgar Hoover’s campaign to defame, infiltrate, and criminalize Black nationalist organizations and their leaders, Shakur was incarcerated for four years prior to her conviction on flimsy evidence in 1977 as an accomplice to murder.”

Angela Davis: An Autobiography

If They Come in the Morning, Angela Davis, ed.

“With race and the police once more burning issues, this classic work from one of America’s giants of black radicalism has lost none of its prescience or power

One of America’s most historic political trials is undoubtedly that of Angela Davis. Opening with a letter from James Baldwin to Davis, and including contributions from numerous radicals such as Black Panthers George Jackson, Huey P. Newton, Bobby Seale and Erica Huggins, this book is not only an account of Davis’s incarceration and the struggles surrounding it, but also perhaps the most comprehensive and thorough analysis of the prison system of the United State.

Since the book was written, the carceral system in the US has seen unprecedented growth, with more of America’s black population behind bars than ever before. The scathing analysis of the role of prison and the policing of black populations offered by Davis and her comrades in this astonishing volume remains as pertinent today as the day it was first published.

Featuring contributions from George Jackson, Bettina Aptheker, Bobby Seale, James Baldwin, Ruchell Magee, Julian Bond, Huey P. Newton, Erika Huggins, Fleeta Drumgo, John Clutchette, and others.”